A general strike? Here? In New Brunswick?

It happened, or at least a version of a general strike happened, back in the spring of 1992. And the even more surprising part of the story is that it was successful.

With storm clouds gathering on the labour relations front in New Brunswick these days, the 1992 general strike may be more than an historical curiosity.

The situation thirty years ago was not all that different from what we see today. Unions were insisting that they needed to negotiate contracts that protected and improved living standards for their members. And employers were saying that they did not have the resources to do that. This was especially true in the public sector, which was reeling from deep cuts in transfer payments to the provinces that had been imposed by the federal government.

The confrontation came to a head in the public sector in 1991, just as Premier Frank McKenna was completing his first term in office. As a major employer, the province had a power that no other employer had – the ability to bring in laws and regulations to shore up their position.

To prove their point, McKenna’s government passed an Expenditure Management Act that suspended scheduled public sector wage increases. Thousands of people turned out to protest in front of the legislature. A Coalition of Public Employees was formed, bringing together several of the affected unions, including nurses and teachers. A complaint that tampering with collective agreements was a violation of international labour standards went to the International Labor Organization, and eventually there would be a decision in favour of the unions.

But Premier McKenna did not wait before deciding to repeat the experiment the next year, after winning re-election against a divided opposition. A second Expenditure Management Act was introduced in 1992, extending existing contracts for two more years, with pay increases limited to no more than 1 and 2 per cent. It looked like the “exceptional” measures of 1991 were going to be more permanent.

The Coalition of Public Employees returned to action, and their rallying cry focused directly on the premier, under the slogan “In McKenna No Trust.” The message went out through the social media of the 1990s, including buttons, banners, and billboards as well as radio and television spots and full-page newspaper ads. The theme was that the province was abusing its legislative authority by overturning legal contracts and suspending collective bargaining: “The McKenna Government under the guise of financial responsibility, is dismantling the values that make New Brunswick worth living in.”

The campaign reached its peak at the end of May, when members of the New Brunswick Nurses Union and the Canadian Union of Public Employees voted to go on strike unless the government withdrew the legislation. Meanwhile, delegates to the annual meeting of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour, many of them from unions not directly involved in the dispute, voiced support for the public sector unions, up to and including a general withdrawal of services – a diplomatic term for a general strike.

As it turned out, mediators were at work behind the scenes, and when it came, the general strike did not go beyond the membership of CUPE. The first week of June saw picket lines at government offices, schools, hospitals, highway garages, liquor stores and other operations. The government quickly secured injunctions against mass picketing. And the premier did not hesitate to escalate the situation by calling for the decertification of CUPE as a bargaining agent and threatening to sue the union for millions of dollars in lost sales at the liquor stores.

But McKenna had underestimated the support for the unions among the general public. As the strike continued, several of his closest advisors convinced him to sit down with CUPE national president Judy Darcy. Under a complicated arrangement, the government agreed to exempt CUPE from the wage freeze while the union agreed to a contract extension and a modest wage increase at a later date. Also, there would be no fines or other reprisals against union members who went out on the illegal strike. The deal allowed the province to claim the settlement was fiscally responsible, while the union could say they had fought the government to a standstill and defended union rights.

Technically, the four-day general strike that took place in 1992 was a sectoral strike involving workers in a large province-wide union where many groups had a shared grievance against their employer. But the political element was obvious, as these workers were taking drastic action to reject the assumption that the province’s fiscal difficulties could or should be downloaded onto public employees. There were also underlying concerns about McKenna’s “real agenda” of reduced services, unfair taxation, privatization, and other initiatives to promote a “business-friendly” environment. All this was conditioned by the belief that McKenna’s predecessors in the premier’s office, Richard Hatfield and Louis Robichaud, had treated organized labour as an essential partner in provincial development.

General strikes are very unusual in our labour relations system. Since the time of William Lyon Mackenzie King, the system has been constructed to try to avoid strikes. Today, workers covered by union contracts are required to remain at work unless they have gone through all the stages necessary to reach a legal strike position. That may take years, and even then, as nursing home workers have discovered in the recent past, they may still be declared essential workers or otherwise prevented from exercising the strike option. Strikes continue to be by far the least common method of settling labour disputes.

Our laws have long recognized the legitimacy of unions, and the Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that collective bargaining is protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Most workers take pride in their work and their value to society. In return, they expect to have fair wages, reasonable conditions, and respect from their employers. When these are denied, and denied on a large scale, as happened in 1991 and again in 1992, workers know they have to stand together.

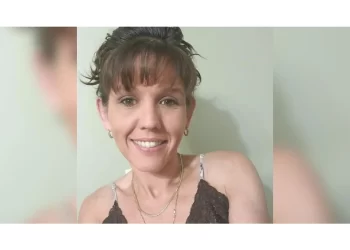

David Frank is the author of Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour.

![‘Anything but Conservative’ is preferred election outcome for many First Nations voters [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MTIMar312025-120x86.jpg)