Irving Peterpaul, from Elsipogtog First Nation, 50, has been ice fishing for about 47 years. His mother taught him to ice fish when he was “no bigger than a bucket,” said Peterpaul.

“Just grab a stick on the shore, put the line on, put the hook in the water, and we’re all fishing.”

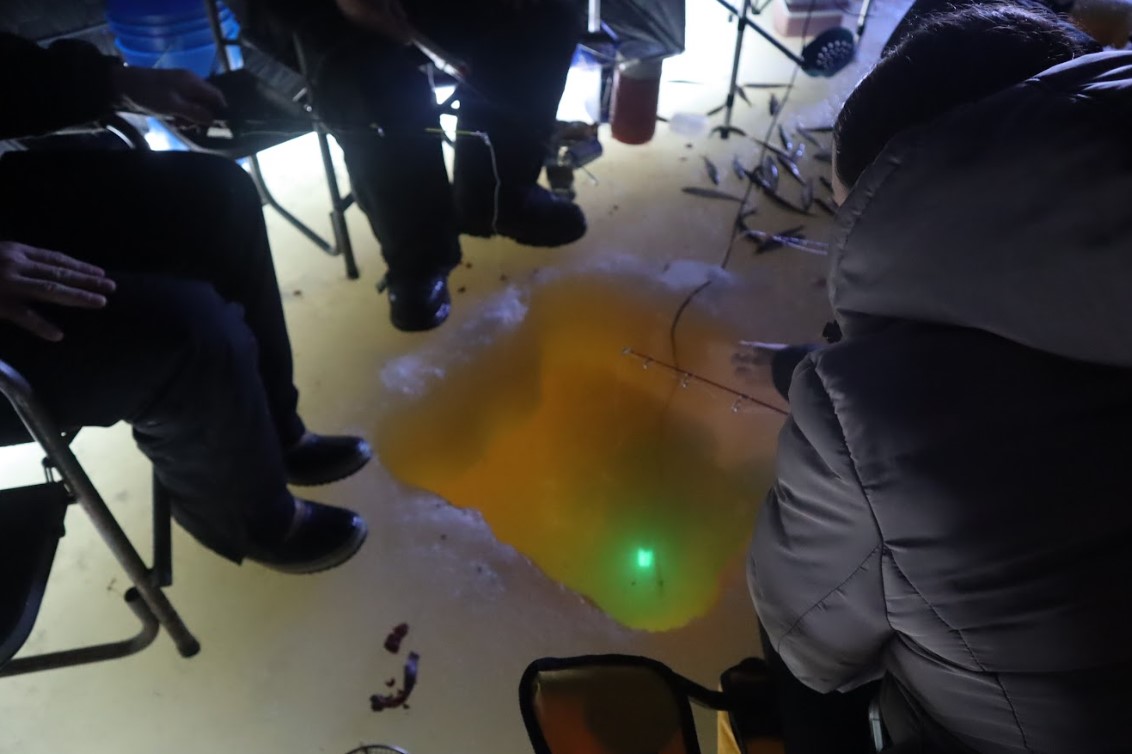

I was at “Herman’s,” which is what locals call the area of the ice by the Elsipogtog shore on the Richibucto River.

As we spoke, fish swam around the hole. Everyone watched as the smelt poked at the hooks. Occasionally, one would bite Peterpaul’s line, and he would haul it up, remove the fish from the hook and place it in a pile, all while answering my questions.

Throughout our conversation, Peterpaul added about six more to his pile. “In my younger days, we used to fish wide in the open. We used to use an axe to make our holes, and we’d sit out there,” he reflected.

Peterpaul often brings Elders and youth to ice fish. When I spoke with Peterpaul, he was accompanied by international students from the high school. “Today’s a good day,” said Peterpaul “We had a two-week drought.”. He set up a large tent to accommodate the students.

Behind Peterpaul sat a small space heater, keeping the tent warm. Inside the fishing hole in front of him, a green light floated in the water. He explained that the green light is meant to attract fish.

Despite the technological advances, Peterpaul noted that he catches fewer fish than in the past.

“We’d get a bucket-full in an hour,” recalled Peterpaul. “Yes, the fishing is slowing down, and the ice is getting thinner. We used to have three, four feet. Now, we’re only like 17 inches today.”

The length of the season is another change, Peterpaul remembers the ice-fishing season beginning in October; now, he says, it starts between late November and mid-December.

Lyle Vicaire, an environmental scientist from Elsipogtog First Nation, said possible effects of climate change on ice fishing include “different movements in the fish, less ice, less days of fishing.”

In general, Vicaire has noticed a number of environmental changes in New Brunswick. “You see the animals moving: the moose are moving, the deer are moving. The fish are moving; the fish are gone.”

Vicaire is the founder of Sikniktuk Climate Adaptation, which started as a government-funded project. “The purpose was to buy the land for future conservation and if needed, for salt marsh restoration,” said Vicaire. “Salt marshes are very important to Mi’kmaw people, very important to mitigation.”

Mitigation, as used in environmental science, means reducing the impacts of climate change. The salt marshes serve an important environmental purpose. “They take in a lot of CO2 from the air and in the ocean, and they keep it locked in the marshes.”

Vicaire described his work in climate adaptation as, “nature-based solutions and trying to mitigate living with it. I say climate adaptation because climate change is done.”

Peterpaul goes ice fishing almost every day during the season. “Oh, I just love being out here, the quietness, peacefulness, and it brings people to you too,” said Peterpaul.

I asked Peterpaul what he thinks is causing the changes mentioned. “Probably global warming, I would imagine,” Peterpaul responded. “Well, you gotta adapt,” said Peterpaul. “They like a certain temperature, as long as we have ice, we got the fish, but we lose the ice, we lose the fish.”

“Science, as much as we have that we know, we’re just not catching up to what’s actually happening right now. For me, it’s more about using nature to adapt to the climate crisis and to keep on going,” said Vicaire. He spoke about Siknktuk Climate Adaptation’s future. “Well, I’m going to keep doing what I’m doing, I’m going to keep the study going.”

The project has evolved over the years to include public outreach, “we’re figuring out as we go and doing it with Indigenous communities and regular training,” said Vicaire. “So, it was kind of like a stepping stone into a broader direction.”

Peterpaul often shares his catch with the community.

“I usually fish for Elders or friends who can’t be here. I take care of who I can when I can.” “We’re just keeping tradition alive,” said Peterpaul. “They love it. They’re all happy, and they’re smiling. They invite you in for a feed too, sometimes.”

“Growing up, I would have a pile of fish and the person next to me would have a few,” Peterpaul said. He shares his ice-fishing journey on his YouTube channel and was featured on CBC’s Land and Sea. “That’s what happens when you love what you do.”

“Ice fishing brings people here, you know, from all over the world,” said Peterpaul. “And as you see, new people love it, eh? They enjoy it,” said Peterpaul, and he gestured to the students fishing.

Anna-Leah Simon is a St. Thomas University student and an intern with the NB Media Co-op from Elsipogtog.

![‘Anything but Conservative’ is preferred election outcome for many First Nations voters [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MTIMar312025-350x250.jpg)

![Interview with Anita Joseph, winner of the New Brunswick Human Rights Award [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/AnitaJoseph-2-350x250.jpg)

![Elsipogtog comic convention to return in 2026 following first-ever event [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-28-at-13.47.38-350x250.jpg)