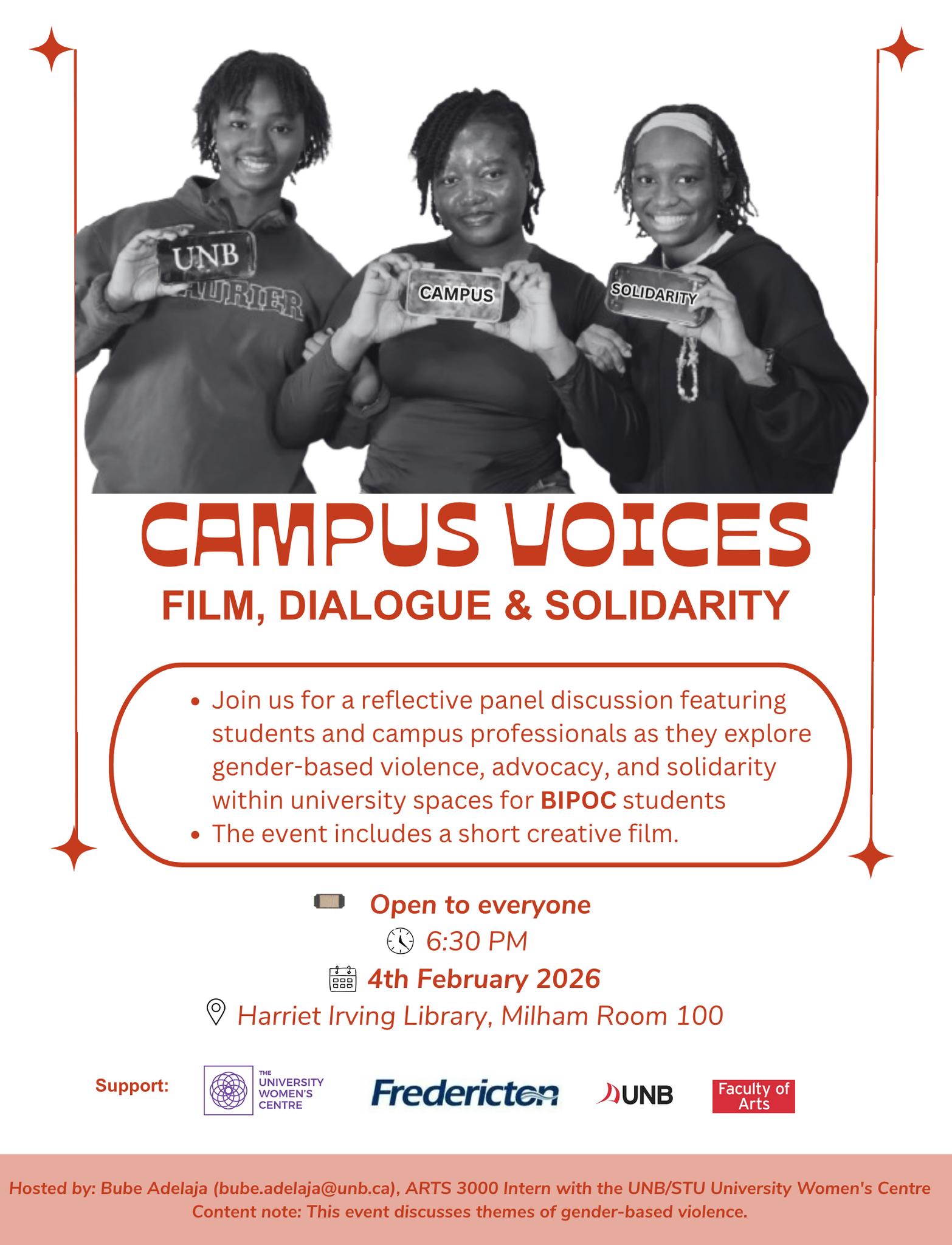

An event titled “Campus Voices: Film, dialogue and solidarity” was held on Feb. 4 at the Harriet Irving Library at the University of New Brunswick.

When speaking of the origin of project, organizer Bube Adelaja revealed that she overheard a conversation between international students about UNB being “very White.” When thinking about it, Bube Adelaja came to the conclusion that “safety and belonging are not just ideals (…) and are not always guaranteed.”

Bube Adelaja is a student completing an Arts internship with the UNB/STU University Women’s Centre.

The evening started with the screening of a short documentary film, titled “Breaking Cycles, building safety” that features BIPOC members of Fredericton’s campuses on their sense of security. The film, directed by Bube Adelaja, was skillfully edited to include students’ responses to a set of questions like “how do we change the culture of silence around issues like sex for grades?” and framed with questions meant to provoke discussion.

The panel featured four speakers, Sophia Etuhube, a journalist from CBC New Brunswick, Joanne Owuor, from the UNB Human Rights and Equity Office, Courteney DeMerchant, from Sexual Violence New Brunswick, and Ezinne Adelaja, a recent NBCC graduate, mom and immigrant working in the Horizon Health Network.

Panelists were first asked if there were enough structures for support on campuses.

Ezinne Adelaja provided the following metaphor: “you get to see the building, but you don’t see how to get inside.” She specified that BIPOC students are in a special situation: “we know we are good, but we feel like we are second class citizens (…) we are afraid of being treated like trash.” For her, communication is key to understanding the processes, to “locate where the resources are.”

For Owuor, the support on campus is centered around “institutional processes and not students’ lived realities.” Students don’t understand “how systems work,” sometimes until after they are done their studies. Owuor said the better question would be about “access (…) without fear, or without fear of penalty,” which can come in the form of retaliation for complaining, fear of losing their student status, etc.

DeMerchant specified that for support, “quantity matters but quality is important too.” She asked: “who is championing the resources, are they trauma-informed”? For her, it is difficult for the Sexual Violence New Brunswick organization to be an accomplice while working in a larger oppressive system.

DeMerchant rebounded on what Ezinne Adelaja stated: “who are the people working in the building and what do they know about the people coming into it?” She added that there needs to be work done for her own organization to change.

Etuhube relayed an anecdote about meeting two girls who couldn’t believe she was a journalist and expressed they had not been supported in their dream of becoming a journalist. Etuhube indicated: “I felt so bad, they had a lot to say (…) a lot of BIPOC students struggle (…) don’t feel confident.” Despite her current age, status and job, Etuhube said: “I know how intimidating it can be.”

The panelists were then asked “how can the university communities be better allies to BIPOC students”?

Etuhube said that when students arrive at UNB, “they should be equipped to feel confident, give them all the resources that they need.” Students need to be asked: “do they feel seen, do they feel safe, (…) do they feel included.” She added: “at the end of the day, everyone is looking for a sense of belonging.”

DeMerchant questioned the definition of allyship and from whose point of view: “it’s a continuation of trust (…) people can also break it.” She added: “To be an active ally, means taking accountability and (…) choosing to use your voice to advocate for other folks.”

For her part, Owuor joked that she “breaks into hives” when she hears the word “ally”; she wants “accomplices” in the work that needs to be done. For her, being an accomplice means “intervening vocally when harm occurs (…) being proactive,” and “accepting discomfort (…) an inevitable part of the process.” Discomfort, for Owuor, “is where you’re doing to discover the work that needs to happen.”

For Etuhube, accomplices must “build trust (…) are you really interested in them”? This needs to happen at the institutional level, according to Etuhube.

Owuor takes a human rights lens: “what am I willing to risk to hold up someone else’s rights”? For her, silence is not neutral, especially “from those with power (…) it’s a reinforcement of harm.” For international and BIPOC students, silence is what has been taught and must be overcome. Ezinne Adelaja suggested finding a “safe space” to express yourself.

Ezinne Adelaja declared that immigrants themselves need to recognize that they are “not worthless,” and, in fact, they “are bringing immense value to the community.” She added: “you should never [accord respect to others] to your detriment.” People must “know who you are and what you stand for” and they must “show up.” Others must ask themselves, “how much of their culture have you learned”? Etuhube asked: “Do you know me (…) do you know my struggles?”

The final question asked of the panelists was: “What are some solutions to build solidarity?”

DeMerchant said solidarity starts with “listening (…) solidarity is listening (…) centering intersectionality.” This begins with “allowing for places to rest and gather.” Owuor added “joy” as crucial to these spaces.

For international students, Owuor says everything “feels so tentative, overwhelming and scary,” because of the added layer of immigration status. Owuor cautioned the attendees: “the system has not been built to see you fully,” and advised “it’s important to push back, (…) asking questions, filling out the surveys.”

Owuor mentioned solidarity is present when “rights are proactive and not reactive,” when “processes are clear.” At the university, all “students must understand their rights, how to access them and how to leverage them (…) without fear.” Owuor stressed people must “ask for what [they] need.” Like Owuor, Ezinne Adelaja specified that students should “hold the authority accountable,” ask for action, short, medium and long-term changes. People must have “a vision and focus,”and “stay true to who you are.”

Etuhube stated people “want to know your stories.” In her experience as a journalist, “one of the most empowering things you can do for people is to tell their story right.” For Etuhube, “uninterrupted listening, creating the right spaces” is key to people feeling comfortable in doing this.

Attendees, mostly BIPOC community members from the university and immigrants, expressed the difficulties in adapting to the “greener pastures” in Canada for people coming from places of colonialism and trauma. They reiterated the importance of listening and communication in forming relationships of solidarity, and of “amplifying the voices” heard within events like these.

The City of Fredericton’s Community Inclusion Office awarded Bube Adelaja an Anti-Racism Youth Microgrant in order to support this project and event. This is an exciting new initiative for the office, and part of the City’s Anti-racism Action Plan.

Sophie M. Lavoie is a member of the NB Media Co-op’s editorial board.

![‘Anything but Conservative’ is preferred election outcome for many First Nations voters [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MTIMar312025-120x86.jpg)