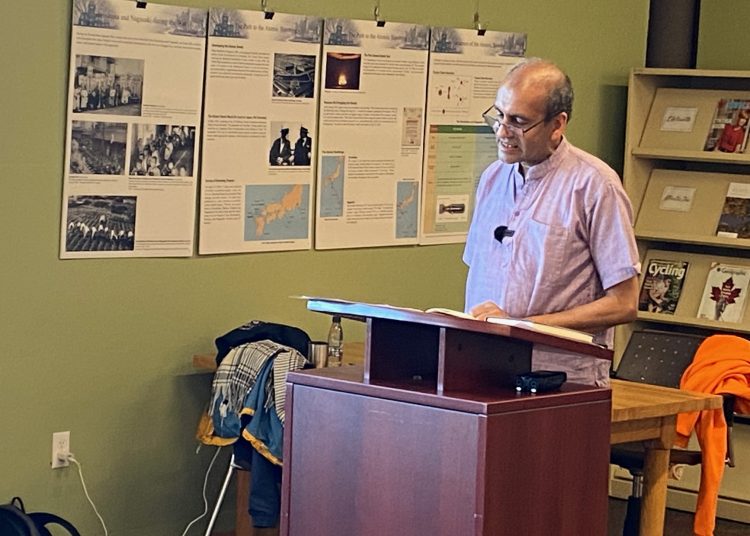

An expo titled “80 Years of the Nuclear Age: Remembering Hiroshima and Nagasaki” opened on Oct. 3 at the Fredericton Public Library. To inaugurate the expo, curated by the Hiroshima Memorial Peace Museum, a national expert on the nuclear industry gave a public lecture.

M.V. Ramana is Professor and Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human Security at the University of British Columbia. He is author of The Power of Promise, on nuclear power in India and Nuclear is not the Solution, about the weaponization of the nuclear industry.

Ramana was introduced by Liam MacDougall, a St. Thomas University student and research assistant with the CEDAR project, one of the sponsors of the exhibition.

Ramana’s own experience with nuclear weapons began when one of his university mentors suggested he do an analysis of what would happen if a nuclear weapon was detonated in an Indian city.

Ramana reminded the crowd present that “there are over 10,000 nuclear weapons in the world (…) at any moment, these weapons can go off.” Most of these missiles, concentrated in nine countries, are more powerful than the bombs that were detonated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. All those countries —U.S., France, Russia, England, India, China, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea— “developed nuclear weapons with plans to use them.”

Ramana gave a synopsis of the history of the creation of nuclear weapons: the Manhattan Project, which led to the bombings during World War II in 1945.

After having helped effectively build the atomic bomb with other European refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, Einstein talked about the “inescapable responsibility” of scientists to inform the world about the possible effects of nuclear weapons for populations to live.

The slogan of the anti-nuclear war movement was “One world or none,” a slogan that was against the rise of fascism in the world at the time.

The posters presented at the expo show the numerous physical and psychological effects of the bombings in Japan. Amongst the immediate physical results of the detonation aftermath: blindness for those watching, the blasting of grains of sand, lethal doses of radiation, the intense shockwave that can bring down concrete structures. Later effects include fires which travel quickly because of strong winds, the production of radioactive fallout, which is a source of radiation exposure which affects people in different ways.

The two cities were targeted in 1945 especially because the creators of nuclear weapons wanted to see the effects of the weapons in a populated city. Although what had happened on site was kept secret, “radiation was a pleasant way to die,” according to higher ups at the time. Even in contemporary research, studies about the climatic effects of a nuclear war are rampant and theories about an apocalyptic “nuclear winter” abound. Ramana cautions it is “prudent to assume the worst.”

After the Cuban Missile Crises in 1963 and the Cold War that ensued (1963-1989), various treaties were signed to try to “curb the destructive capacities and the amounts of weapons made,” said Ramana. However, since the 1990s, there has been no international treaties on nuclear weapons signed, only a few bilateral treaties.

Civil society, especially in countries that don’t have nuclear weapons, have pushed for agreements like the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons adopted by 122 states. The countries that have embraced it, agree not to develop nuclear weapons. This treaty can be used to block the transport of nuclear weapons. “It makes their operations a bit harder,” according to Ramana.

Canada, as an ally of the U.S., has not signed this treaty.

Ramana reminded the public of the difficulties of this issue; the nuclear industry “sits at the intersection of two areas: nuclear energy” and state violence. “The only force that has gone against this is social movements,” he added.

In the city where he lives, Vancouver, there are vestiges of the 1990s anti-nuclear movement spray-painted on the walls of the city, declaring it “Nuclear Free.”

The expo on Hiroshima and Nagasaki will be available for viewing until Oct. 31, at the Fredericton Public Library. Its exhibition is sponsored by St. Thomas University.

Sophie M. Lavoie is a member of the NB Media Co-op’s editorial board.

![Livestream: Social Forum in Wolastokuk — DAY 2 [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Penombre18-4-sur-4-120x86.jpg)

![Palestinian photojournalist documents ‘uninhabitable’ Gaza Strip [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Photo-from-David10-120x86.jpg)