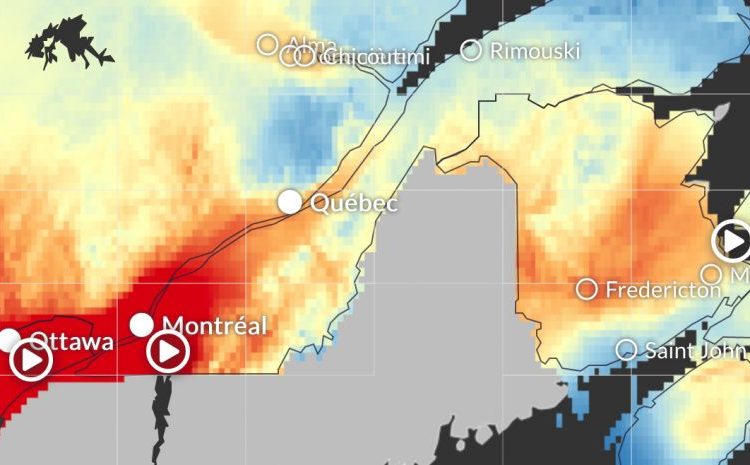

The climate crisis has become a part of our everyday lives. For some of us, this means being confronted with our environmental reality by daily news reports, by articles we read online, or by increasingly hard-to-ignore and erratic weather patterns, as well as their destructive aftermath. But for others, living during the climate crisis does not merely mean living with the knowledge that our world is changing—growing, producing, polluting—at an unsustainable rate, but actually feeling the crisis in climate crisis.

Researchers in New Brunswick, across Canada, and around the world are investigating the effects of the climate crisis on our mental health, including the ways the 2018 Wolastoq (Saint John River) flood has affected and is still affecting the province’s rural river communities.

In June, the Conservation Council of New Brunswick (CCNB) released a report that envisages the future climate of the province and outlines steps residents can take to ensure that their futures are long and far from dire. In “Healthy Climate, Healthy New Brunswickers,” Louise Comeau, director of the CCNB’s climate change and energy program and a research associate at the University of New Brunswick (UNB) in Fredericton, writes, “Mental health professionals are increasingly worried about the psychological effects of climate change.” The report adds that the effects of climate change, including flooding and extended power outages, “can undermine well-being and cause ‘eco-anxiety,’ a ‘chronic fear of environmental doom.’”

The CCNB report references an in-depth 2017 American Psychological Association (APA) assessment. According to the APA’s guide to “Mental Health and Our Changing Climate,” major “acute mental health impacts” include: increases in trauma and shock, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), compounded stress or anxiety, substance abuse, and depression.

Major “chronic mental health impacts” include: higher rates of aggression and violence, more mental health emergencies, and an increased sense of helplessness, hopelessness, or fatalism. They can also include intense feelings of loss.

The APA guide not only outlines the effects of climate change on individuals but also illustrates how “stress from climate change has been observed among various communities.” Communities are beginning to feel “that their sense of self-worth and community cohesion” have decreased in light of altered interactions with their changing environments.

The CCNB report also relies on a 2018 article in the International Journal of Mental Health Systems by Katie Hayes, a researcher at the University of Toronto. Another article published the same year by Hayes, in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, addresses the ways “mental health indicators” might be incorporated into climate change adaptation assessments.

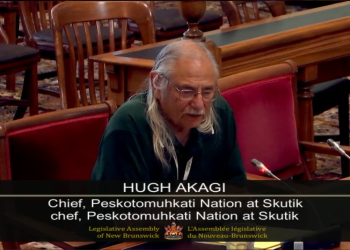

Both the APA assessment and Hayes’s articles spotlight the disproportionate effects of climate change on marginalized communities. According to Hayes, these communities include “Indigenous peoples, children, seniors, women, people with low-socioeconomic status, outdoor labourers, racialized people, immigrants, and people with pre-existing health conditions.” Health effects caused by climate change “amplify existing inequities—placing marginalized people, who generally have contributed the least to the climate change problem, at the greatest risk.”

Julia Woodhall-Melnik, an assistant professor of social science at UNB Saint John, is investigating the ways the Wolastoq flood in 2018 has impacted rural river communities in and around the Kingston Peninsula and Jemseg areas. Looking at mental health effects and shifts in social capital, Woodhall-Melnick and her team surveyed communities that experienced displacement as a result of the flood. The team’s findings have yet to be published.

According to the New Brunswick Emergency Measures Organization, between 2,000 and 3,000 people were displaced from their homes during the flood.

Displacement causes what many researchers have termed “solastalgia,” or the pain experienced from physical dislocation or from the assault on or transformation of a home place. The province’s river communities have a distinct connection to place, and, according to the APA, displacement can leave displaced communities “literally alienated, with a diminished sense of self and increased vulnerability to stress.” Rural communities, inherently alienated from the immediate financial, physical and mental health, and emergency service benefits of larger municipalities, are all the more vulnerable to stress brought about by a changing climate.

But it’s a mistake to believe that residents who are not physically displaced by flooding are exempt from lingering mental health effects. Those whose homes are not flooded may feel something like “survivor’s guilt,” because they cannot or could not substantially help others.

Mental health concerns as they relate to the climate crisis are sticky issues, not because we lack the knowledge or resources to affectively tackle each—and both, together—but for social and political reasons.

Mental health and climate change both have certain political and social stigmas that make acting on them undeniably difficult. Some or most of the world has accepted that we are, indeed, in the midst of a climate crisis. However, often this acceptance comes at a psychological distance: for those of us living in geographical locations not yet profoundly affected by extreme weather events, it’s a change that will become apparent at some far and future date; it’s a global problem, not a local one. Hayes cites sociologist Anthony Giddens, who calls this distancing the “Giddens Paradox.”

Citing George Marshall, author of Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change, Hayes writes that our reluctance to act “is reinforced by the Western political discourse on climate change as a future-facing problem that intentionally overlooks the centuries of industrialization, fossil fuel consumption, and land degradation that contribute to anthropogenic climate change.” This idea is echoed by Swedish activist Greta Thurnberg’s January proclamation, “Our house is on fire. I am here to say, our house is on fire.”

The palpable tension created between the political and social denials of the climate crisis and the energetic “we must act now” rhetoric of climate change researchers and activists is as ceaseless as it is confusing. We’re experiencing more than just weather whiplash. We’re experiencing a whiplash of personal and political agency.

Additionally, writes Hayes, attributing “climate-related extreme weather to mental health outcomes is also challenging because there are few visible indicators of trauma when people are experiencing mental illness, mental problems, or affirmative mental health; as such, it becomes more difficult to establish direct cause and effect relationships.”

But all is not lost. According to Hayes, there are “positive psychological consequences of extreme weather events, like feelings of compassion, altruism, sense of meaning, post-traumatic growth, or even increased acceptance of climate change and engagement with climate mitigation.”

Mental health professionals and other provincial support systems in New Brunswick are in a position to better help rural communities along the Wolastoq and around the province cope with and prepare for the worsening effects of the climate crisis. As Comeau writes in the CCNB report, “We ask stakeholders interested in protecting New Brunswickers’ health to encourage the provincial government to make physical and mental health protection and promotion a driving force behind climate change mitigation and adaptation planning and implementation.”

Lauren R. Korn is a research assistant for the RAVEN project Summer Institute and an M.A. student of Creative Writing at the University of New Brunswick.

![Researcher presents renewable energy plan for the Maritimes [video]](https://nbmediacoop.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Ralph-Torrie-video-clip-350x250.jpg)